With her abilities limited and her choices even more constrained, Joyce Slaughter wasn’t sure what her daughter would be able to do once she moved on from her special education classroom. Beginning a conversation in Cobb County in 1975 about the options for people with impairments in finding jobs, Slaughter, along with teacher Bobbie Knopf, not only helped her daughter but thousands of people with special needs build a future, through the creation of a new nonprofit driven to the task. The teacher and the mother first formed an advisory committee. Then they sought the backing of Atlanta Falcons linebacker Tommy Nobis, who had worked to bring the Special Olympics to Georgia, and in 1977, the nonprofit organization Tommy Nobis Center, now known as Nobis Works, was born.

Humble Beginnings

“From its humble beginning in a donated construction trailer behind then-Northside High School, then to the basement of a vacated Sandy Springs elementary school, today Nobis Works has served more than 24,000 youth and adults with all types of disabilities and other barriers to employment, such as illiteracy, homelessness and substance abuse,” says Connie Kirk, the organization’s only CEO.

The center means so much to the people it helps. Take Ray Charles Simms for example. Blinded by a chemical accident at work at the age of 32, Simms found purpose again when he discovered Nobis Works more than a decade ago, says marketing director Karen Carlisle. Now, Simms takes three buses and a train—a three-hour commute one way—from College Park to get to work at Owens & Minor, one of several businesses that partners with Nobis Works. Carlisle says the center offered to help him find a job closer to home, but he likes his work. And he loves serving as a mentor to new job trainees, “giving hope to someone new almost every day,” she adds.

That hope is what Nobis Works is all about. “When I was a kid in Texas, I tossed the football every day with a neighboring boy who had Down syndrome. Ever since, I’ve had a special place in my heart for folks with special needs,” says Nobis, who is known as “Mr. Falcon.” “I focus my energy today as a volunteer board member, opening doors wherever I can to help create jobs for youth and adults with disabilities and other barriers to employment,” Nobis says of his role in the organization today. “Those we serve wouldn’t come to us if they didn’t want to work. They’re going to do everything within their power to get that job. It’s our job to help them become confident, successful and independent members of America’s workforce.”

A Big Economic Impact

While the nonprofit began as a way to train and help young adults with developmental disabilities to enter the workforce, it has expanded to help people with other problems entering the job market. From physical or mental disabilities to issues with literacy or even homelessness, the mission of Nobis Works has expanded to youth and adults with just about any employment barrier. For example, Carlisle recounts the story of a doctor whose hand injury forced her to sell her practice, and Nobis Works helped her embark on a new career.

In 2013, the organization helped 986 individuals, placing 246 into meaningful jobs, and in its 36 years more than 24,000 people have been served. “It makes a big economic impact,” Carlisle adds. The impact on Cobb’s people and its businesses are much greater than the statistics bear out, Carlisle points out, because not only are hundreds of people each year gaining a paycheck, but they are also leaving government support programs and becoming self-sufficient.

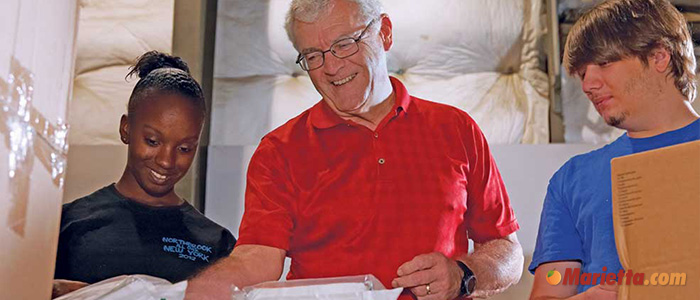

The local business community feels the benefit too, says Matt Porter, the regional director of operations for Owens & Minor, which uses a team of five to 15 Nobis Works clients at its Kennesaw facility, which is dedicated to distributing medical products and supplies. Porter praises the work of job coach Mary Maloney, who has matched the job needs to the abilities of Nobis clients, ensuring success for the company and the people. “It is really difficult to put this in words that will reflect accurately and tell the full story. They make us better. As individuals, as a team, as a company,” Porter says. “Their dedication to their assignments is extraordinary and our customers understand and appreciate their near perfect degree of accuracy.

“When you see what they have overcome and achieved in their lives, it is inspiring,” he adds. “The Nobis team makes us strive for even more. It also makes us stop and appreciate all that we have and take for granted every day of our lives.”

In addition to Owens & Minor in Kennesaw, Nobis Works has also carefully matched clients with jobs at Dobbins Air Reserve Base, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Housing and Urban Development offices. Most recently, the nonprofit paired with Asbury Automotive on its “Café Blends: Blending Autism into the Workplace” project. The partnership, forged in 2012, provides jobs to people on the autism spectrum as baristas at three North Atlanta Nalley dealerships, as well as locations in Greenville, S.C., and Tampa, Fla.

Looking Forward

Nobis continues to stay dedicated to helping others find jobs, but it hasn’t always been easy, especially in recent years. Because the past five years of high unemployment and a stagnant economy have made it more difficult to pair clients with the best employment opportunities out there, Kirk and her team has to think outside the box. “In 2009, when employment was at an all-time low, we took the bull by the horns and decided to create our own jobs rather than trying to find jobs for people with disabilities,” she says. Nobis Works launched its own enterprise, known as ReWorx. The electronics recycling operation not only fulfills a need in the community, but it employs 67 people with disabilities and other employment barriers. Recycling about 1 million pounds of e-waste each month, the operation brings in money that helps support the rest of Nobis Works services, taking the burden away from the philanthropy, which was also hit by the economy. “This program brings a triple bottom line: social, environmental and economic,” Kirk says.