Ask any Atlanta-area gastronome, and they’ll likely tell you that food trucks currently are the hot topic in the culinary world. And the metro area seems to be taking notice, with venues like Smyrna’s “Food Truck Tuesdays,” Kennesaw’s “Dinner at the Depot” and the Atlanta Food Truck Park emerging all over the city.

“Atlanta was a bit slow to become involved in this more-recent food truck movement,” says Brenda Hurley, director of catering for Willy’s, a chain of restaurants that primarily uses its food trucks for catering. “[Food trucks] provide small, local vendors with a venue to sell their food products, which appeals to consumers’ desire to buy locally. The mobility of food trucks also can be convenient for customers, and it’s fun for patrons to track down their favorite trucks.”

Additionally, food trucks represent a business model that’s renowned for being sustainable, minimalist and agile. This phenomenon, however, also signifies the re-emergence of an old business practice—mobilized street food vending practically dates back to the advent of the automobile, albeit perhaps re-imagined and retooled for more sophisticated, health-conscious palates.

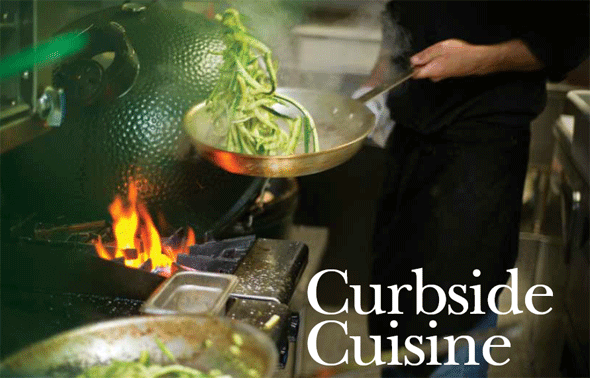

Field-to-Street

Some observers have noted the sudden resurgence of food trucks may be partially reactionary in nature. For decades, the marketplace has been saturated with processed foods and large corporate restaurants. By contrast, many food truck operators are independent businesses offering locally grown produce as part of the so-called “field-to-table” (or, in this case, “field-to-street”) culinary idiom.

“It’s hard to find natural, fresh and well-made food,” explains Terry Hall, the proprietor of Happy Belly Curbside Kitchen, which was recently ranked among the “26 Healthiest Food Trucks in America” by Greatist.com. “There are so many chains and so much food that comes out of a box; you know, [foodservice distribution powerhouse] Sysco makes everything now. My wife and I decided to make a lifestyle change when our daughter was born, and we just got so frustrated with [trying to find healthy food options] that we decided to start making it ourselves and bring it to people.”

Greg Smith is president of the Atlanta Street Food Coalition, which is an advocate for food trucks throughout the metro area. According to Smith, customers seem to view food trucks as an alternative to the many corporate brick-and-mortar restaurants that have proliferated throughout the nation. “With every new shopping center that goes up, it seems like the same restaurants are in them,” he says, “and food trucks are these independent, edgy and interesting operations that don’t necessarily fit that corporate model. So people are getting excited about something new, and I also think they just like the opportunity to get outdoors with friends and family.”

The impetus driving growth among food trucks seems to be multi-layered. In many major metropolitan cities, ever-increasing traffic congestion and tightening schedules make it difficult for workers to take lunch breaks. Subsequently, this creates opportunities for enterprising food trucks. “People are time-strapped,” says Hall. “Every year, Japan and the United States are tied for the two industrialized societies that work the most and have the least time off, and a lot of people are working through their lunch hour.”

To see this principle in action, Hall says, one needs only to see the foot traffic that trucks like Happy Belly routinely receive when visiting the Cobb Galleria. “There’s something like 6,000 employees [at the Galleria], and probably 2,000–3,000 of them come down to the truck every Tuesday for lunch,” he explains. “That’s a direct result of the convenience factor. And I also think the value proposition of a food truck is very, very high as well.”

Logistical Nightmare or Regulatory Headache?

In many senses, these wheeled restaurants operate within a micro-economy that’s relatively shielded from the current recession. While truck operators don’t take the same sort of beating as high-overhead, brick-and-mortar restaurants, both Hall and Smith are quick to caution they’re faced with a very different set of obstacles. “Food trucks are more agile, but the logistics are also more challenging,” says Hall. “Matt Helms [from Twisted Taco] and I were talking about this on the radio recently, and we both agree that running a brick-and-mortar is way easier than running a food truck. The mobility aspect of it is great, but it adds challenges like you wouldn’t believe.”

To this end, Hall says, planning has to be more thorough because many different factors come into consideration. Seemingly mundane things like weather, power generation, road conditions, construction sites and traffic can all affect day-to-day operations. “You’ll be driving somewhere and you have to slam the brakes,” says Hall. “Then all of a sudden, your cooler flies open and food flies all down the aisle, and you’ve lost all that product. We’re also on our second generator, and we’ve only been open four months.”

According to Hurley of Willy’s, success in the food truck business can be as simple as operating clean and attractive vehicles, providing friendly service and great food, and offering a rich experience to guests. But even under the most ideal conditions, the permitting process for food trucks can be particularly complicated—especially in the metro Atlanta area, where operators are forced to deal with a complicated cluster of regulatory agencies and governmental entities. “You need a health permit and business licenses [usually with each individual city, unincorporated area or township],” explains Smith. “Sometimes, you also have to have a vendor license that’s issued by the police department, and you also have to deal with zoning issues at the city level. As it stands right now, the food truck permitting process in Atlanta touches on all these different areas, whereas a fixed business often only has to deal with one or two of these.”

According to Hurley of Willy’s, success in the food truck business can be as simple as operating clean and attractive vehicles, providing friendly service and great food, and offering a rich experience to guests. But even under the most ideal conditions, the permitting process for food trucks can be particularly complicated—especially in the metro Atlanta area, where operators are forced to deal with a complicated cluster of regulatory agencies and governmental entities. “You need a health permit and business licenses [usually with each individual city, unincorporated area or township],” explains Smith. “Sometimes, you also have to have a vendor license that’s issued by the police department, and you also have to deal with zoning issues at the city level. As it stands right now, the food truck permitting process in Atlanta touches on all these different areas, whereas a fixed business often only has to deal with one or two of these.”

Complicating matters is the fact that all these bureaucratic agencies and governmental groups don’t necessarily communicate with one another, says Hall. As a result, some rules and regulations are in direct opposition to each other, which can frustrate food truck owners. “The one thing that I try and get people to understand,” he says, “is that there’s really nobody out there who’s ‘anti-food truck’—except, you know, maybe the occasional restaurant owner or somebody—but as far as governmental folks go, there’s not an antagonist there. It’s just layers and layers of regulation and different groups. It makes it very difficult to get anything done.”

An Emerging Food Truck Mecca

While Smith admits that there may not currently be a wide range of food truck friendly sites in Cobb County at this point, he believes that support for them is gaining momentum. The Smyrna City Council recently voted to approve Food Truck Tuesdays, which began in July of this year.

Despite some concerns regarding taxation and licensing for the trucks among the council, the measure passed after Mayor Max Bacon cast the tie-breaking vote. Significantly, this was the first time Bacon had been called upon to do so since 2007. “It’s up to the city of Smyrna if they want the trucks to have business licenses, and sales tax is required by state law,” adds Smith.

For his part, Hall says he’s been “extremely humbled” by the support his business has received from Smyrna and Food Truck Tuesdays. “We’re sort of one of the anchors; it’s right down the street from our office,” he explains. “It’s the best food truck venue in the city. The crowds they’re getting there are better than the ones we have at 12th and Peachtree in Midtown.”

Aside from Smyrna, some other food-truck friendly sites have emerged in the Cobb County area as well, including the Paper Mill Village in East Cobb and Dinner at the Depot in Kennesaw. Both events feature live music, and they count Hall and Happy Belly among the food trucks they regularly host. Marietta has also been making considerable efforts to establish a venue of its own.

Of course, Cobb County’s food trucks still face similar challenges to what they’d be facing elsewhere in the metro area. “They’re going to need a fixed kitchen space to operate from, and of course that’s going to have to be permitted by Cobb County for their mobile unit,” says Smith, “and the challenge comes down to finding the proper location to operate, and it needs to have enough foot traffic to justify all the trouble to get permitted.”

Even given these obstacles, Hall says Cobb County is still among the metro area’s most food truck friendly counties. “The people of [Cobb] just love the idea of food trucks, and they think it’s really cool to have them in their community,” he says. “We started working with Cobb County to get our permits and it only took us about three weeks. Their attitude was, ‘Here’s what you can and can’t do. Now get to work.’”

So where would one start in getting permits, ect to start a food truck in Cobb County? Will I need a health permit (yes), business license (for sales tax I believe I will), and a vending permit? Does Cobb have different regulations than City of Atlanta as far as how many locations I could vend from, how preprepared food items need to be packaged, etc. Cant find much online for Cobb. Thanks!!

Hi Cristin,

One of the best resources for this is the Atlanta Street Food Coalition, online at:

http://www.atlantastreetfood.com/

How do I go about starting a food truck park?