The Marietta Confederate Cemetery, established in 1863, holds the distinction of being one of the oldest Confederate cemeteries in the United States. Its origins are rooted in the heart of the Civil War, as it was established to provide a final resting place for Confederate soldiers who had valiantly given their lives in defense of their homeland.

The Marietta Confederate Cemetery, established in 1863, holds the distinction of being one of the oldest Confederate cemeteries in the United States. Its origins are rooted in the heart of the Civil War, as it was established to provide a final resting place for Confederate soldiers who had valiantly given their lives in defense of their homeland.

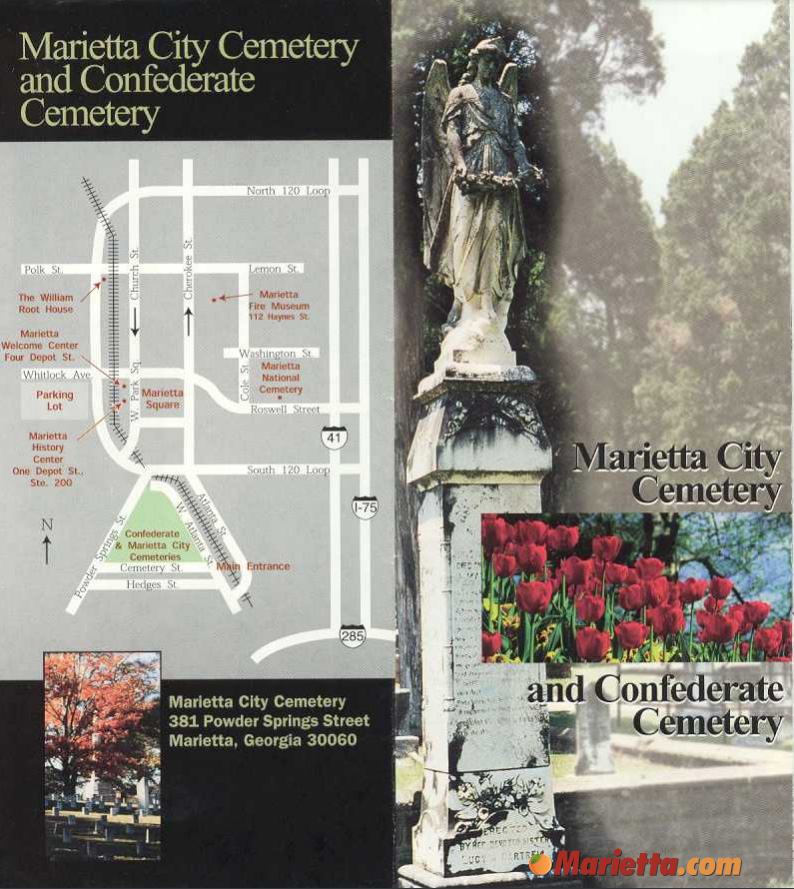

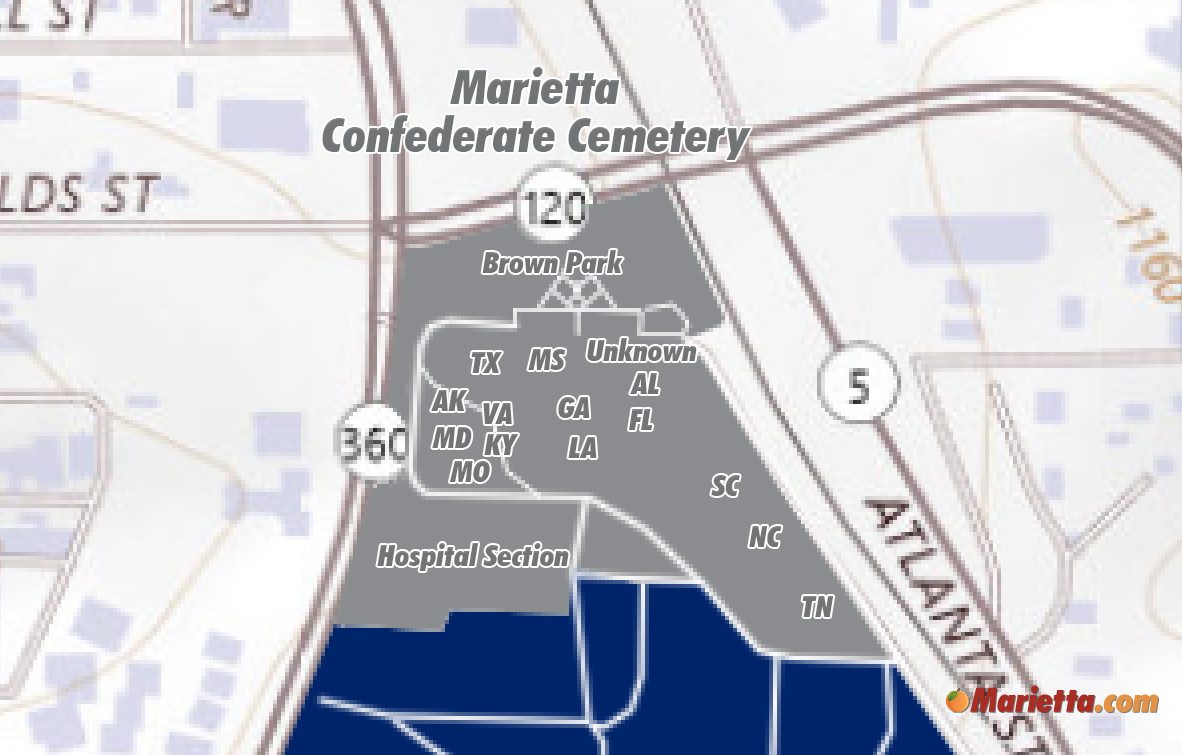

Situated adjacent to the older Marietta City Cemetery, the Marietta Confederate Cemetery is prominently positioned on a hill overlooking the downtown square from the southern vantage point.

The 1861-1865 conflict between North and South forced many men to leave their homes to defend Southern soil. Although many eventually returned to their loved ones, others came to rest here in the Marietta Confederate Cemetery. The cemetery began as the burial ground for 20 Confederate soldiers who tragically lost their lives in a train wreck north of town. It was later expanded to serve as the final resting place for Confederate soldiers who had been cared for in nearby hospitals and those who had participated in the battles of the Atlanta Campaign, including significant engagements such as Kolb’s Farm and Kennesaw Mountain.

The 1861-1865 conflict between North and South forced many men to leave their homes to defend Southern soil. Although many eventually returned to their loved ones, others came to rest here in the Marietta Confederate Cemetery. The cemetery began as the burial ground for 20 Confederate soldiers who tragically lost their lives in a train wreck north of town. It was later expanded to serve as the final resting place for Confederate soldiers who had been cared for in nearby hospitals and those who had participated in the battles of the Atlanta Campaign, including significant engagements such as Kolb’s Farm and Kennesaw Mountain.

After the Civil War, a solemn new mission unfolded, as more than 3,000 Confederate soldiers who had perished elsewhere were carefully recovered and reinterred within its hallowed grounds. The soldiers buried here come from all 11 Confederate states as well as soldiers from Maryland, Missouri, and Kentucky.

By 1902, the wooden markers that had initially marked their resting places had deteriorated, resulting in the loss of many names over time. In a poignant gesture of remembrance, these markers were replaced with simple yet dignified marble counterparts.

Within the cemetery, visitors are greeted by rows of meticulously aligned headstones that serve as a solemn tribute to the bravery and unwavering dedication of those who fought for the Southern cause.

Over the years, the Marietta Confederate Cemetery faced financial challenges and fell into disrepair, in contrast to the nearby Marietta National Cemetery, which received federal support from the Department of Veterans Affairs. The maintenance and restoration of the Confederate Cemetery depended largely on donations, primarily from the citizens of Marietta. As time took its toll, the area required substantial attention.

However, in a heartwarming testament to the dedication of local groups and Marietta citizens, the past few decades have witnessed a remarkable transformation. Through their tireless efforts, repairs and improvements have been diligently undertaken, restoring the Marietta Confederate Cemetery to its former glory. Today, this historic site is maintained as both a place of remembrance and a commitment to preserving the memory of those who made the ultimate sacrifice in defense of their beliefs and homeland.

Location:

Marietta Confederate Cemetery is located in between Marietta City Cemetery and Brown Park.

Hours:

Open daily from dusk to dawn

Admission:

Free

Phone:

(770) 429-1115

Address:

395 Powder Springs St,

Marietta, GA 30064

You might also be interested in:

Welcome to Marietta’s Garden of Heroes:

“Here Lie the Men in Gray”

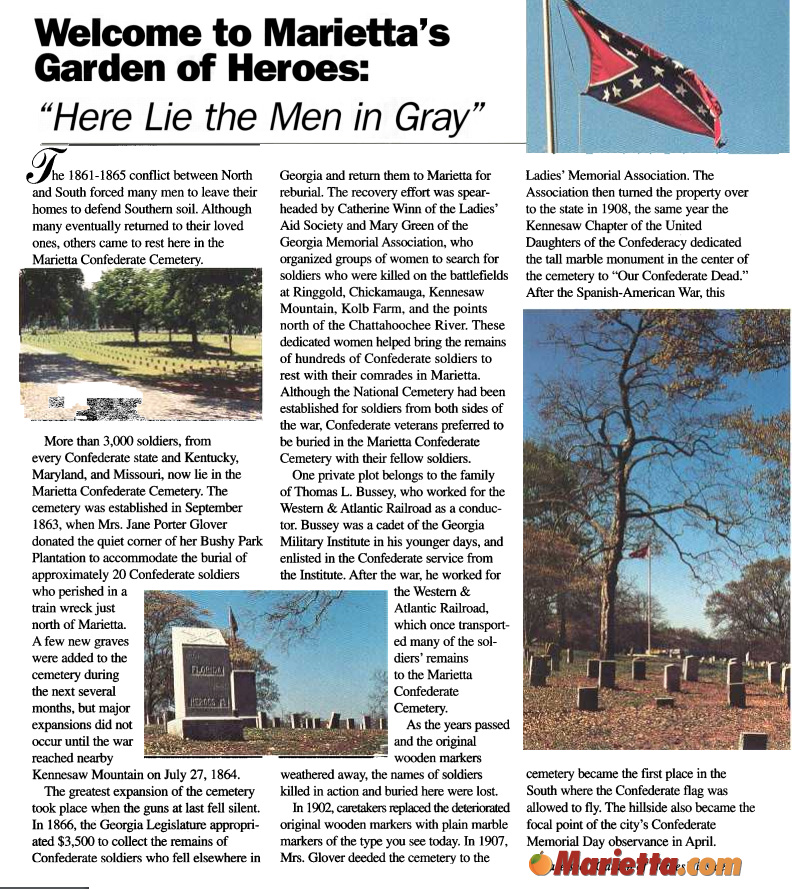

The 1861-1865 conflict between North and South forced many men to leave their homes to defend Southern soil. Although many eventually returned to their loved ones, others came to rest here in the Marietta Confederate Cemetery.

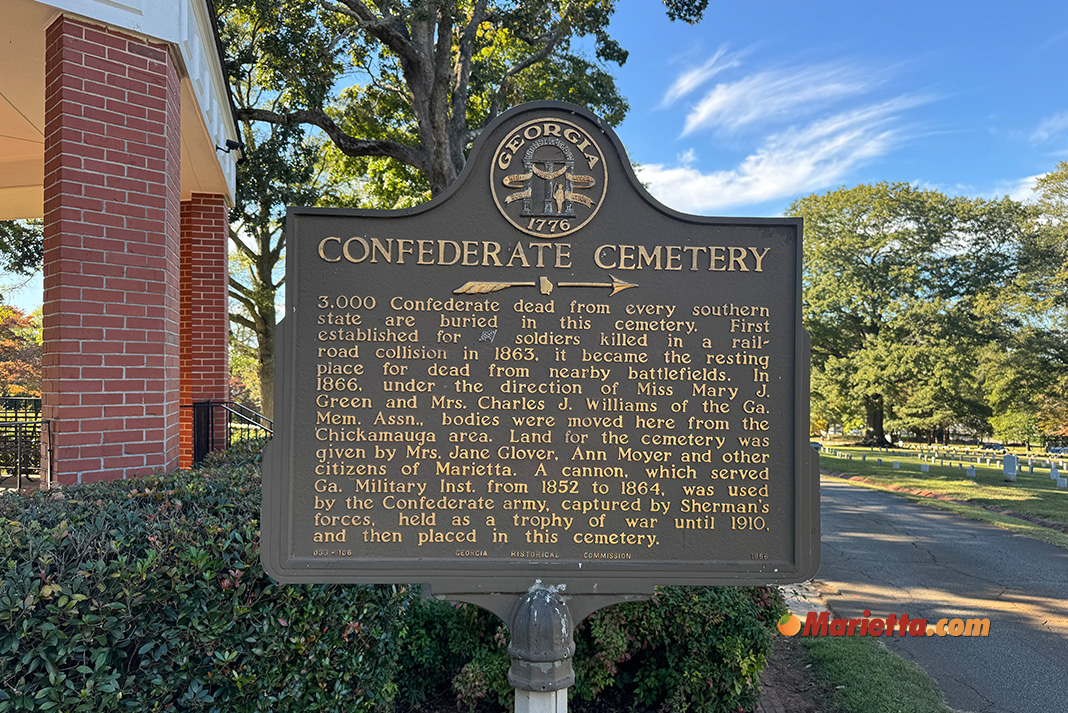

More than 3,000 soldiers, from every Confederate state and Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri, now lie in the Marietta Confederate Cemetery. The cemetery was established in September 1863, when Mrs. Jane Porter Glover donated a quiet corner of her Bushy Park Plantation to accommodate the burial of approximately 20 Confederate soldiers who perished in a train wreck just north of Marietta. A few new graves were added during the next several months, but major expansions did not occur until the war reached nearby Kennesaw Mountain on July 27, 1864.

The greatest expansion of the cemetery took place when the guns at last fell silent. In 1866, the Georgia Legislature appropriated $3,500 to collect the remains of Confederate soldiers who fell elsewhere in Georgia and return them to Marietta for reburial. The recovery effort was spearheaded by Catherine Winn of the Ladies’ Aid Society and Mary Green of the Georgia Memorial Association, who organized groups of women to search for soldiers who were killed on the battlefields at Ringgold, Chickamauga, Kennesaw Mountain, Kolb Farm, and the points north of the Chattahoochee River. These dedicated women helped bring the remains of hundreds of Confederate soldiers to rest with their comrades in Marietta.

Although the National Cemetery had been established for soldiers from both sides of the war, Confederate veterans preferred to be buried in the Marietta Confederate Cemetery with their fellow soldiers.

One private plot belongs to the family of Thomas L. Bussey, who worked for the Western & Atlantic Railroad as a conductor. Bussey was a cadet of the Georgia Military Institute in his younger days, and enlisted in the Confederate service from the Institute. After the war, he worked for the Western & Atlantic Railroad, which once transported many of the soldiers’ remains to the Marietta Confederate Cemetery.

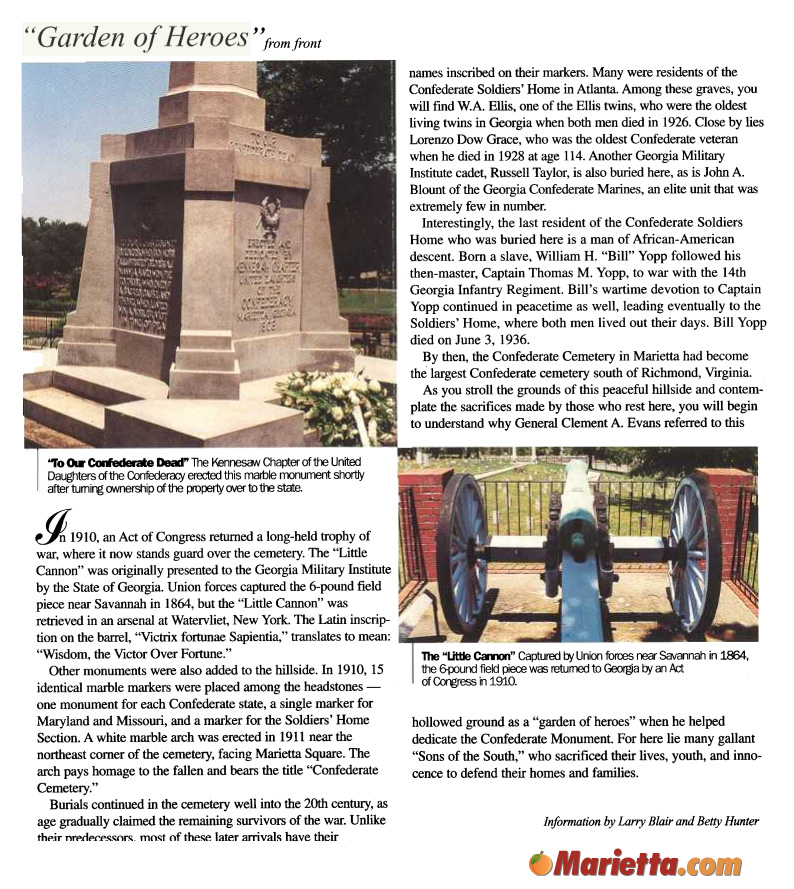

As the years passed and the original wooden markers weathered away, the names of soldiers killed in action and buried here were lost. In 1902, caretakers replaced the deteriorated original wooden markers with plain marble markers of the type you see today. In 1907, Mrs. Glover deeded the cemetery to the Ladies’ Memorial Association. The Association then turned the property over to the state in 1908, the same year the Kennesaw Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy dedicated the tall marble monument in the center of the cemetery to “Our Confederate Dead.”

After the Spanish-American War, this cemetery became the first place in the South where the Confederate flag was allowed to fly. The hillside also became the focal point of the city’s Confederate Memorial Day observance in April.

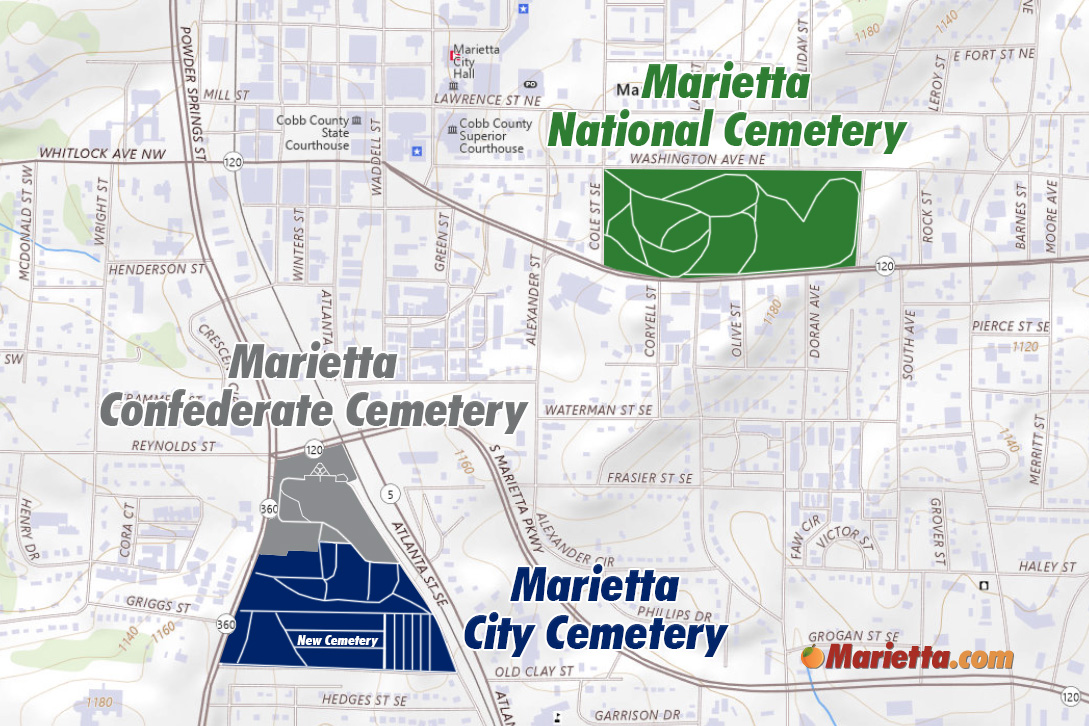

In 1910, an Act of Congress returned a long-held trophy of war, where it now stands guard over the cemetery. The “Little Cannon” was originally presented to the Georgia Military Institute by the State of Georgia. Union forces captured the 6-pound field piece near Savannah in 1864, but the “Little Cannon” was retrieved in an arsenal at Watervliet, New York. The Latin inscription on the barrel, “Victrix fortunae Sapientia,” translates to mean: “Wisdom, the Victor Over Fortune.”

Other monuments were also added to the hillside. In 1910, fifteen identical marble markers were placed among the headstones—one monument for each Confederate state, a single marker for Maryland and Missouri, and a marker for the Soldiers’ Home Section. A white marble arch was erected in 1911 near the northeast corner of the cemetery, facing Marietta Square. The arch pays homage to the fallen and bears the title “Confederate Cemetery.”

Burials continued in the cemetery well into the 20th century, as age gradually claimed the remaining survivors of the war. Unlike their predecessors, most of these later arrivals have their names inscribed on their markers. Many were residents of the Confederate Soldiers’ Home in Atlanta. Among these graves, you will find W.A. Ellis, one of the Ellis twins, who were the oldest living twins in Georgia when both men died in 1926. Close by lies Lorenzo Dow Grace, who was the oldest Confederate veteran when he died in 1928 at age 114. Another Georgia Military Institute cadet, Russell Taylor, is also buried here, as is John A. Blount of the Georgia Confederate Marines, an elite unit that was extremely few in number.

Interestingly, the last resident of the Confederate Soldiers Home who was buried here is a man of African-American descent. Born a slave, William H. “Bill” Yopp followed his then-master, Captain Thomas M. Yopp, to war with the 14th Georgia Infantry Regiment. Bill’s wartime devotion to Captain Yopp continued in peacetime as well, leading eventually to the Soldiers’ Home, where both men lived out their days. Bill Yopp died on June 3, 1936.

By then, the Confederate Cemetery in Marietta had become the largest Confederate cemetery south of Richmond, Virginia.

As you stroll the grounds of this peaceful hillside and contemplate the sacrifices made by those who rest here, you will begin to understand why General Clement A. Evans referred to this hollowed ground as a “garden of heroes” when he helped dedicate the Confederate Monument. For here lie many gallant “Sons of the South,” who sacrificed their lives, youth, and innocence to defend their homes and families.

– Information by Larry Blair and Betty Hunter